2-18: The Geography of Identity

When a Place Becomes Part of You

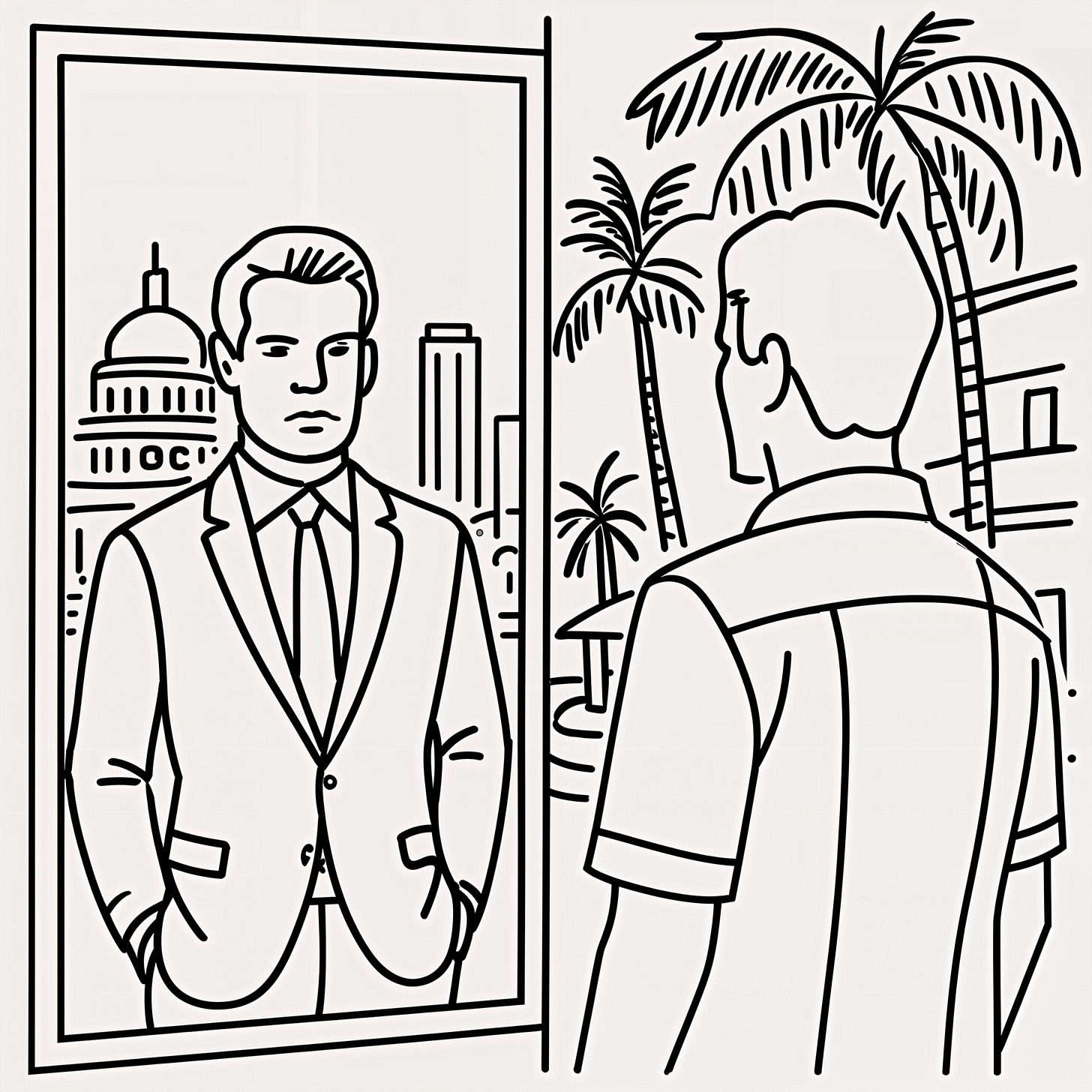

When I first moved from Washington, D.C. to Miami, I thought of myself as someone simply living in Miami, not yet one with the city. I had yet to shed my property-tax bearing Virginia license plate, and my work wardrobe leaned heavily towards dark suits, and most of my social life carried over from long-distance connections back in D.C. I was present in this new city, but I wasn’t part of it. For the first long while, I felt like a tourist who had overstayed his welcome.

After a while though, something shifted. Maybe it was when I found myself sweating through another August afternoon and realizing I had stopped checking the weather. Perhaps it was the moment I caught myself defending Miami to a New Yorker who made a blanket-statement comment about there being no real professionals in the city. While I agree there are few, there are certainly more than none. I remember joking to myself one day that I had officially become 51% Miami. I didn’t know if that moment came six months in or two years later, but there was a tipping point where the city stopped being the latest background and began to feel like a piece of me.

Identity is not static, and geography has a way of shaping us more than we realize. Cities impress themselves on us through their seasonality, climate, pace, architecture, and even the attitudes of the people who call them home. D.C. made me measured and professional; Miami loosened my grip, encouraged my individuality, my passion for the arts, and rewarded spontaneity. When I compare photos of myself from those years, I see not just a younger version of me, but two different people who carried themselves differently in part due to the places they lived. After settling into Miami, I've found that I carry myself with more confidence and boldness, grateful that my past self had the courage to start fresh in a city where I knew no one.

The question of when you “become” part of a place is difficult to pin down. It is not about days or years marked off on a calendar, but about how deeply you internalize the rhythms of your surroundings. For some, it happens the first time they feel homesick while traveling. For others, it might never come, even after decades in one place. A city becomes part of you when leaving feels like leaving a piece of yourself behind and when you start to recognize that you identify more with your new city than with the one you left.

I sometimes wonder what percentage of me is Miami now. Sixty? Seventy-five? The math is less important than the idea that we are subconsciously rebalancing ourselves by the day. Moving does not erase what came before, but it adds a new layer, like a sediment layer of rock in a canyon. Each place we’ve lived influences how we carry ourselves today.

If fate is the co-author of our choices, then geography is the stage where those choices play out. Both fate and geography guide the story of who we become, one through the doors that open unexpectedly and the other through the unnoticed surroundings of daily life. Maybe becoming “of a place” is not about hitting a feeling of a "majority," but about recognizing when a city has seeped into your identity so thoroughly that leaving it would mean adding another layer of sediment to who you are.